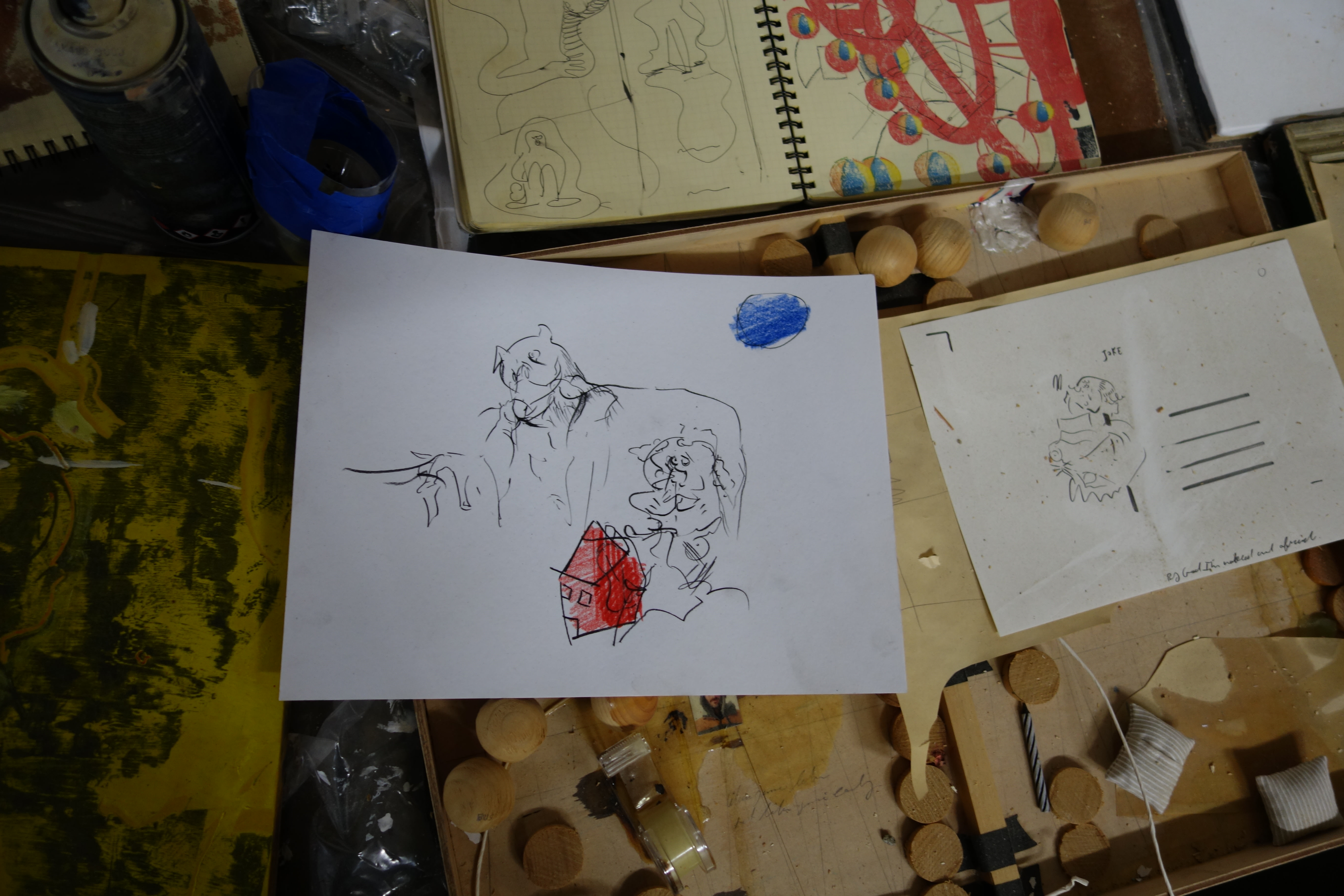

Oranges vs Them comprises a new series of works on paper, made by Uri Aran during recent months. Employing diverse materials, ranging from oil pastel, graphite, coloured pencil and newsprint, the artist registers a complex array of scenographies. Intuitive markings, human and anthropomorphic forms, and handwritten notations appear to respond to fragments of readymade imagery, suggestive of a broader narrative impulse. Originating as an everyday practice in the artist’s studio, the drawings’ interwoven elements amount to form enigmatic yet impish tensions and exchanges between characters, unfolding as new realms within the page. In turn, the works have initiated a collaborative response in the writings of others, including the accompanying text to this exhibition by Mason Leaver-Yap.

Oranges vs Them comprises a new series of works on paper, made by Uri Aran during recent months. Employing diverse materials, ranging from oil pastel, graphite, coloured pencil and newsprint, the artist registers a complex array of scenographies. Intuitive markings, human and anthropomorphic forms, and handwritten notations appear to respond to fragments of readymade imagery, suggestive of a broader narrative impulse. Originating as an everyday practice in the artist’s studio, the drawings’ interwoven elements amount to form enigmatic yet impish tensions and exchanges between characters, unfolding as new realms within the page. In turn, the works have initiated a collaborative response in the writings of others, including the accompanying text to this exhibition by Mason Leaver-Yap.

Waiting in 1990

The receptionist smiles and leans over the front desk. She passes me a blank colouring-in book and a handful of pens and pencils. I can wait over there. Printed with chunky lines on white paper, the cover depicts a schematic of the same waiting room in which I’m standing. A generic image of a child has been inserted next to the reception desk. Child and desk are dwarfed by a perfectly rotund cartoon droplet standing next to them. The droplet looks down at the child with googly eyes and a wide grin. It has two arms and two legs. It wears shoes. It says something via a speech bubble that I assume is welcoming. In the next page, the droplet gestures with its gloved hands to other rooms beyond the frame, inviting the child to take a guided tour. Unclenching my fist, I survey my colouring options. I pick the red pen first, but it has already run out, leaving only a brittle squeak and pink smear. I fill in the fat droplet with green pencil instead.

There is a subsection of kink called ‘Vore’. To count as Vore, the thing or image has to be consuming itself. The Vore genre is primarily considered a sexual fetish, but representations aren’t always schlocky cannibalism. In fact, it’s a fairly common occurrence in everyday life: butchers adorn their vans with comical pigs snaffling sausage rolls; ice cream parlours decorate their part of the sidewalk with sculptural effigies of a big drippy cone licking a mini drippy cone; cartoons of burgers are often, by dint of their bun-shaped mouths, already munching down on a beef patty with tomato and lettuce. After Jesus and his disciples, smiley face ecstasy pills and their consumers are perhaps the most mainstream human symbol of Vore culture: eat the happiness you want to be.

Part-distraction, part-education, the book is a Vore-ish attempt to assuage panic – panic of blood, panic of needles, panic of HIV /AIDS and Hepatitis, panic of death. It seeks to consume attention and, in doing so, habituate a narration of blood. The duration required to fill in this book also allows for the other practical things that happen here to take place with less interruption: the time it takes an adult to donate a pint of blood, the time taken by a nurse to administer an infusion, the time needed to interview someone as a transfusion candidate.

As well as the small child and the big droplet, there are other characters that appear in later pages of this colouring-in book. A red blood cell presents a challenge for my remaining colouring options – green pencil already taken, so it goes purple. Boringly, a white blood cell is meant to stay blank, but I fill it in orange highlighter anyway. Some of the flashier disposable pens that the receptionist gave me come bearing logos I’ve seen around here before: Glaxo, Pfizer, Bayer, Astra – companies with a stake in the droplet’s story. But after testing each of the pens, I find that their ink is either just black or blue biro. I toss the book aside after encountering a platelet and ask the receptionist if I can have one of the patient cookies.

– Mason Leaver-Yap